Kristen Hargis & Marcia McKenzie, MECCE Project

Photo Credit: Rafael Henrique from stock.adobe.com

The body was created in 1988 with help and support from the United Nations Environment Program and the World Meteorological Organization (WMO). All member countries of the United Nations and the WMO can participate in the Panel, which includes 195 countries.

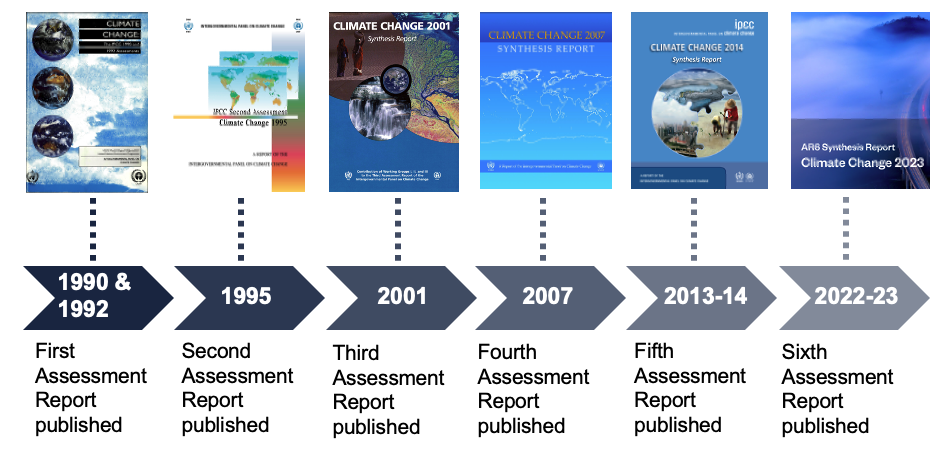

The IPCC is perhaps the most well known for its assessment reports, which are the cumulative work of hundreds of experts around the world. To write the assessment reports, experts review thousands of academic papers before compiling summaries of the evidence base on climate change causes, impacts, and future risks, as well as options for climate change adaptation and mitigation. They also produce special reports on specific topics (e.g., the 2018 special report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C). All their reports are reviewed prior to publication by governments and expert reviewers to ensure they represent the latest scientific evidence.

If you are familiar with the IPCC, you may also be thinking, “Didn’t they just release an assessment report last year?” If so, you’re right. The authors of the IPCC assessment reports are divided into three working groups. Working Group I addresses the physical science basis of climate change, Working Group II addresses climate change impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability, and Working Group III addresses climate change mitigation. One assessment report cycle includes reports from each of the three working groups, as well as a synthesis report, which integrates the findings from all three working groups for a total of four reports. The four reports are published at different times over one to two years. A full assessment report cycle is published every five to nine years.

This brings us back to where we are now. The IPCC assessment report that was released today was the final synthesis report for the sixth cycle of IPCC assessments.

Or perhaps you wonder, “I know these reports aim to influence climate policy, but what impact do they actually have?” The first IPCC assessment released in 1990 is credited as contributing to development of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) (Ravindranath, 2010). Each year the UNFCCC brings together 198 member nations at Conference of the Parties (COP) meetings to assess current progress on climate change and adopt new measures to support action to mitigate and adapt to climate change. For instance, it was at COP21 in 2015 that the Paris Agreement was adopted, which is a legally binding international treaty adopted by 194 Parties. These Parties agreed to reduce greenhouse gas emissions so that global temperatures would not rise above 2°C of pre-industrial levels, while also pursuing efforts to limit warming to 1.5°C.

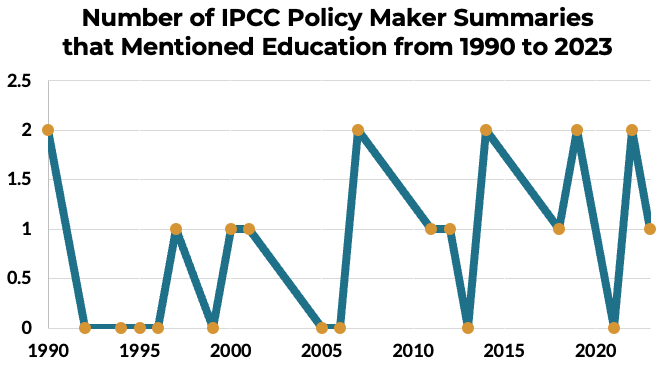

The IPCC reports also shape public debate on climate change, and world leaders often quote report findings in speeches and decisions. In particular, policymakers and scientists make heavy use of the policymaker summaries included in each assessment and special report (Howarth, & Painter, 2015). These summaries are used by policymakers to provide background and to justify policy decisions. In fact, the policymaker summaries are so important, they are approved line by line by member countries, in consultation with the scientists who write the reports.

Photo Credit: SL Photography from stock.adobe.com

Photo Credit: Mongkokhon from stock.adobe.com

“The social, economic, and cultural diversity of nations will likely require educational approaches and information tailored to the specific requirements and resources of particular locales, countries, or regions.”

– IPCC Summary for Policymakers 1990

Education is often mentioned when referring to education bodies as potential stakeholders, or in listing sectors key to climate mitigation and adaptation action. When education is discussed in more depth, the focus is usually on changing behaviours or sharing information related to climate change.

Only 16% (5/31) of policymaker summaries include mention of Indigenous knowledge in relation to education, all of which were published in 2014 or later. The IPCC policymaker summaries (and reports) have historically included a limited focus on Indigenous knowledge, even though the incorporation of Indigenous knowledge alongside Western science is essential for addressing climate change (Ford et al., 2016).

“Education, information, and community approaches, including those that are informed by [I]ndigenous knowledge and local knowledge, can accelerate the wide-scale behaviour changes consistent with adapting to and limiting global warming to 1.5°C. These approaches are more effective when combined with other policies and tailored to the motivations, capabilities and resources of specific actors and contexts (high confidence).”

– IPCC Summary for Policymakers (2018)

It is striking that none of the policymaker summaries for IPCC Working Groups II (impact, adaptation, and vulnerability) or III (mitigation) mention climate justice in relation to education since issues of justice are central to any strategy to assist those most vulnerable in adapting to and mitigating climate change impacts. The IPCC reports also have room for growth in relation to the inclusion of diverse voices in their assessments. Previous reports have been criticised for “includ[ing] a geographical bias favoring experts from the global north, a gender bias in favor of men, a disciplinary bias in favor of the natural sciences over the social sciences and humanities, and finally, a cosmological bias favoring western science over [I]ndigenous knowledges” (Chakraborty & Sherpa, 2021).

So, where do we go from here? Considering the impact the IPCC reports have on international climate policy and the need for more climate change education to create the social and political will for climate action (Walfisz, 2021), it is a matter of crucial importance that the policymaker summaries include a stronger focus on education, including in relation to Indigenous knowledge and climate justice.

How can I learn more?

For more information about what quality climate change education can look like, check out the following resources:

About the Authors

Dr Kristen Hargis is a MECCE Project Postdoctoral Scholar who specializes in quality climate change education policy and practice. She is currently coordinating a UNESCO commissioned project analyzing curricula from at least 75 countries for the inclusion of climate change education. She also coordinates the Project’s US Landscape Analysis, which explores state-level uptake of climate change education in policy across primary, secondary, and higher education in partnership with the North American Association for Environmental Education. Since 2013, she has worked with the MECCE Project and its host, the Sustainability and Education Policy Network (SEPN), on a range of projects including several UNESCO consultancies and SEPN’s Canadian Landscape Analysis. She holds a Ph.D. in Environment and Sustainability from the University of Saskatchewan and received her M.Ed. in Educational Foundations from the University of Saskatchewan.

Dr Marcia Mckenzie is the MECCE Project’s Director and Principal Investigator and Director of the Sustainability and Education Policy Network (www.sepn.ca). She is Professor in Global Studies and International Education in MGSE at the University of Melbourne, Australia; and Professor on leave at the University of Saskatchewan, Canada. Dr. McKenzie is a member of the Royal Society of Canada’s College of New Scholars, Artists, and Scientists. Her research program includes both theoretical and applied components at the intersections of comparative and international education, global education policy research, and climate and sustainability education, including in relation to policy mobility, place, affect, and other areas of social and geographic study.

References

1. Ravindranath, N. H. (2010). IPCC: Accomplishments, controversies and challenges. Current Science, 99 (1), 26-35.

2. Vasileiadou, E., Heimeriks, G., & Petersen, A.C. (2011). Exploring the impact of the IPCC assessment reports on science. Environmental Science & Policy, 14, 1052-1061.

3. Howarth, C. & Painter, J. (2015). Exploring the science-policy interface on climate change: The role of the IPCC in informing local decision-making in the UK. Palgrave Communications, 2(1), 1-12.

4. Ford, J. D., Cameron, L., Rubis, J., Maillet, M., Nakashima, D., Willox, A. C., & Pearce, T. (2016). Including Indigenous knowledge and experience in IPCC assessment reports. Nature: Climate Change, 6, 349-353.

5. Chakraborty, R. & Sherpa, P. Y. (2021). From climate adaptation to climate justice: Critical reflections on the IPCC and Himalayan climate knowledges. Climatic Change, 167 (49), 1-14., p. 1.

6. Walfisz, J. (2021, September 28). Students take over their classrooms to demand teaching on climate change. Euronews.