Aaron Benavot, Marcia McKenzie, Kate Greer, and the broader MECCE Project team

Global strategies for effective climate communication and education

Strengthening ACE monitoring and evaluation

“Gaps, needs and opportunities for improvement in implementation that have been repeatedly highlighted include … (the) need for more consistency and ambition at the international level, including in relation to monitoring and reporting, to facilitate national ACE implementation, while maintaining flexibility and a country-driven approach.”

The importance of strengthening monitoring, evaluation and reporting was also highlighted by the UNFCCC Secretariat at a workshop on Voluntary Guidelines for Monitoring, Evaluation and Reporting of ACE Activities. Country delegates were introduced to a range of monitoring approaches and tools, including through our Monitoring and Evaluating Climate Communication and Education (MECCE) Project, as they prepared for COP26 and ongoing deliberations on the ACE work programme.

Boat School in Bangladesh, Children in a Class Seated at a Lesson. Credit: Abir Abdullah / Climate Visuals Countdown

Agriculture Education. Credit: US Department of Agriculture / US Department of Agriculture.

Credit: Mike Baumeister on Unsplash

That said, concerns have been raised that new monitoring and reporting frameworks may add administrative and financial burdens to some countries that are already resource constrained, as well as financial obligations to other countries to help cover costs. These are legitimate concerns for designing effective and fair processes within UNFCCC processes. We believe that investment in M&E strategies is fundamental to addressing a range of ACE gaps, in particular limited understanding of what constitutes quality ACE or CCE, a limited and inconsistent global ACE response, and unequal distribution of available funding. This blog post makes the case for increased prioritization of M&E as part of an effective national and international ACE strategy, and highlights the important role of indicators, and key principles in their development.

How do indicators help to increase the extent and impact of ACE?

Robust indicators are essential tools in a well-stocked monitoring toolkit. They act as useful proxy measures for complex systems by measuring distinct aspects of a system and how specific components work together for overall results. They can track progress of system components in ongoing ways (monitoring) and at specific time-points (evaluation). They provide insights that can support status updates of a system, and enhance understanding of the impacts that policies or activities have on decision making. Indicators can also provide valuable input into scenario forecasting and be used to trigger decisions. For example, data from climate modelling can inform the extent to which CCE indicators focus on climate change mitigation or adaptation, and how that may vary over time and region.

United Nations General Assembly Hall in the UN Headquarters, New York. Credit: Basil D Soufi

Indicators can enable national policymakers to establish benchmarks, set measurable targets, and monitor progress across all ACE elements. They also provide transparency that enables non-government stakeholders to make decisions about where to direct their efforts and resources for greatest impact, including in relation to advocacy. At an international level, indicators enable intergovernmental negotiations to proceed based on technically rigorous and consistent data sets rather than country self-reports. A globally applicable set of indicators can thus support an increase in the quantity of quality CCE nationally, regionally, and internationally, by identifying gaps and opportunities, and helping to drive ambition. Yet, no such set of indicators currently exists.

Considerations for CCE/ACE indicator development

The MECCE Project is developing an informative set of indicators to support a broad understanding of the state of CCE/ACE around the world and to foster increased ambition and progress on CCE/ACE. Our approach to indicator development is guided by best practices and considerations identified through a review of the research literature.

We recognise that indicators are politically and culturally rooted, both in their design and their application. More critical perspectives from education and other fields raise concerns about general trends toward indicator use in global governance, specifically in relation to the entities or individuals that determine global indicators and exercise power in national and regional contexts. ‘Data diversity’ is essential so that Global North metrics are not assumed to measure Global South activity and that indicators, and the data types that inform their development, are appropriate and relevant in diverse regions. Others raise concerns about indicators being used in ways that misrepresent progress related to CCE. For instance, science test scores have been used as indicators of sustainable development learning despite research evidence indicating that the acquisition of scientific knowledge does not in and of itself engender capabilities to act.

Flags of Member Nations Flying at United Nations Headquarters. Credit: UN Photo/Joao Araujo Pinto. Creative Commons.

A partnership approach to developing, reporting and reviewing indicators will help to address CCE/ACE concerns. Partnerships generate access to a greater array of data sources and tools, and support country input into data sources and indicators. A partnership approach enables broadening and harmonizing the relevance of the indicators across cultures and regions, and sheds light on diverse factors that influence inputs, outputs, and outcomes,. Furthermore, partnerships are key to responding to financing concerns. As a global research-policymaking collaboration, the MECCE Project is able to pool expertise and mobilize knowledge with tools and data that helps to resource countries’ M&E.

Crucially, we recognise that quantitative and qualitative data go hand-in-hand when seeking to drive meaningful CCE/ACE action through M&E. Monitoring coupled with evaluation provides in-depth insight to countries’ initiatives and the contexts in which they are embedded. The combination enables understanding of how and why particular initiatives have been implemented, and to what effect. Conceptual and contextual information can help to explain indicators and associated targets and to avoid unintended impacts of indicator use. Furthermore, non-specialist decision makers can be encouraged to use indicators if they are communicated alongside case studies. The MECCE Project’s qualitative analyses of CCE captured in case studies and quantitative insight enabled by indicators, will help to enrich understanding of what constitutes meaningful CCE around the world.

The MECCE Project: Working to strengthen CCE/ACE M&E

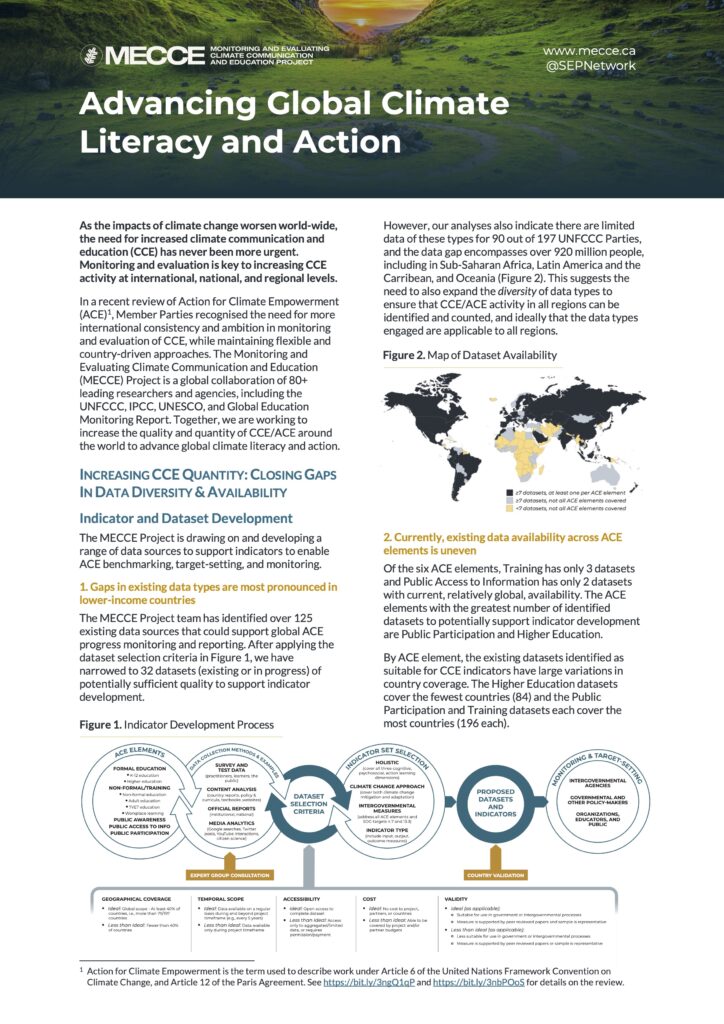

The MECCE Project’s team of multidisciplinary experts is taking up these principles in our work to improve the quality and increase the quantity of CCE globally. To date, we have defined 57 possible indicator areas linked to 32 datasets across the ACE elements. We will be coupling the indicators of ACE-related inputs, outputs, and outcomes with insight from a series of Country Profiles developed in partnership with the UNESCO GEM Report, and with qualitative case studies. Initial insights from the MECCE Project research, including sample indicators, can be found in a new brochure developed for COP26: “Advancing Global Climate Literacy and Action”. The MECCE project invites policymakers, researchers, and practitioners to contact us about country-level M&E and to join our Regional Hubs Network. Together we can continue to strengthen the role of M&E in furthering CCE/ACE ambition and action.

How can I learn more?

More information about the MECCE Project’s indicator development work is available in our brief, “Advancing Global Climate Literacy and Action.”

For more information on the global MECCE Project’s work on climate change communication and education, visit www.mecce.ca.

About the Authors

Dr Aaron Benavot leads the MECCE Project’s Indicator Development Axis, sits on the MECCE Project’s Steering Council, and Leads the project’s Indicator Expert Group and Indicator Working Group. He is a Professor of global education policy in the School of Education at the University at Albany-SUNY. Aaron has co-authored/edited five books and is a contributing author on many UNESCO reports. From 2014-2017, Aaron served as Director of the Global Education Monitoring (GEM) Report, where he oversaw the development of three reports — Education for all: 2000-2015: Achievements and challenges (2015); Education for people and planet: creating sustainable futures for all (2016); and Accountability and Education: Meeting our commitments (2017/8).

Dr Marcia Mckenzie is the MECCE Project’s Director and Principal Investigator and Director of the Sustainability and Education Policy Network (www.sepn.ca). She is Professor in Global Studies and International Education in MGSE at the University of Melbourne, Australia; and Professor on leave at the University of Saskatchewan, Canada. Dr. McKenzie is a member of the Royal Society of Canada’s College of New Scholars, Artists, and Scientists. Her research program includes both theoretical and applied components at the intersections of comparative and international education, global education policy research, and climate and sustainability education, including in relation to policy mobility, place, affect, and other areas of social and geographic study.

Dr Kate Greer is the MECCE Project’s Associate Director. She has worked in the environment and education sectors in both government and non-government organisations in Australia and South East Asia. She managed the team responsible for the Victorian Government’s sustainability education program, ResourceSmart Schools in Australia, and lead the Renewable Energy and Energy Efficiency Partnership (REEEP) in South East Asia and Pacific. Her doctoral research, undertaken at King’s College, London, and supported by the Rosalind Driver Scholarship Fund, examined England’s climate change education-related policy landscape.

References

1. ACE is the term used to describe the body of work related to climate communication and education that is anticipated in Article 6 of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) (1992) and Article 12 of the Paris Agreement (2015).

2. https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/Inf.note_ACE%20.pdf

3. Addison, P.F.E., Cook, C.N., & de Bie, K. (2016). Conservation practitioners’ perspectives on decision triggers for evidence-based management. Journal of Applied Ecology, 53, 1351-1357

4. Davis, K.E., Kingsbury, B., & Merry, S.E. (2012). Indicators as a technology of global governance. Law & Society Review, 46(1), 71-104.

5. Gorur, R. (2017). Statistics and statecraft: Exploring the potentials, politics and practices of international educational assessment. Critical Studies in Education, 58(3), 261-265.

6. Komatzu, H. & Rappleye, J. (2018). Will SDG4 achieve environmental sustainability? Centre for Advanced Studies in Global Education: Arizona.

7. UNESCO GEM Report. (2016). Global Education Monitoring Report: Education for people and planet: Creating sustainable futures for all. Paris: UNESCO

8. Fehling, M., Nelson, B.D., & Venkatapuram, S. (2013). Limitations of the Millennium Development Goals: A literature review. Global Public Health, 8(10), 1109-1122.

9. UNESCO GEM Report. (2016). Global Education Monitoring Report: Education for people and planet: Creating sustainable futures for all. Paris: UNESCO

10. Bubb, P. (2013). Scaling up or down? Linking global and national biodiversity indicators and reporting. In B.Collen, N. Pettorrelli, J. E. M. Baillie, & S. M. Durant (Eds.), Biodiversity monitoring and conservation: Bridging the gap between global commitment and local action (pp. 402-420). Oxford, UK: Wiley-Blackwell.

11. Leadley, P., Pereira, H.M., Alkemade, R., Fernandez-Manjarrés, J.F., Proença, V., Scharlemann, J.P.W., & Walpole, M.J. (2010). Biodiversity scenarios: Projections of 21st century change in biodiversity and associated ecosystem services. Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity, Montreal Technical Series, 50, 1-132.