“Look at things and watch the land and be grateful, thankful. Present. It’s important…

Watch the land. And it will watch you.”

– Nalze (Case Study Participant)

Country: Canada

CCE Types: Training

Climate Change and Futures-Building Through Dene Stewardship Camps

Set on the East Arm of Tu Nedhé, also known as Great Slave Lake, the Indigenous Protected Area of Thaidene Nëné is fast changing but deeply imbued with ancestral knowledge and care. Characterized by rivers and waterfalls, dramatic rock formations, a deep freshwater lake, and the migration of barren-ground caribou, the land has sustained Dënesųłıné for generations.

Established by Łutsël K’é Dene First Nation, the vision for Thaidene Nëné is: Nuwe néné, nuwe ch’anıé yunedhé xa, which means “Our land, our culture for the future” in Dënesųłıné.

With its future orientation, Thaidene Nëné is dedicated not only to care for the land through climatic changes but also to education through land-based stewardship camps.

The Łutsël K’é Dene First Nation prioritizes youth mentorship and employment-oriented learning on the land for the purposes of “ensuring the well-being of the land and our people long into the future.”

Sharing governance over Thaidene Nëné with Parks Canada and the Government of the Northwest Territories, the Łutsël K’é Dene First Nation has long partnered with researchers to host non-formal land-based education programs in the park lands.

Land-based education is not a new mode of education. Indigenous communities have shared and developed knowledge this way for thousands of years. As a longstanding way of knowing and learning, land-based education holds great potential for learning in the face of climate change: by developing understandings of the changing land, strengthening Indigenous thought systems and land relations, and informing decision-making about the land.

Land-based camps, ranging from culture camps to canoe trips, combine traditional Dene knowledge with skills for scientific research and climate adaptation. Cognitive development is supported by learning technical skills learned in relation to both traditional knowledge and western scientific processes. Hands-on technical training such as navigation and plant identification is linked to traditional knowledge. Through Dënesųłinë́ language learning, Dene games, and storytelling by Elders, participants learn about plants, animals, land, water, sacred sites, and places. They learn the history of each region and concerns about shifts in the land, with particular attention to decline in caribou. This leads to deep and integrative understanding of climate impacts on the local land.

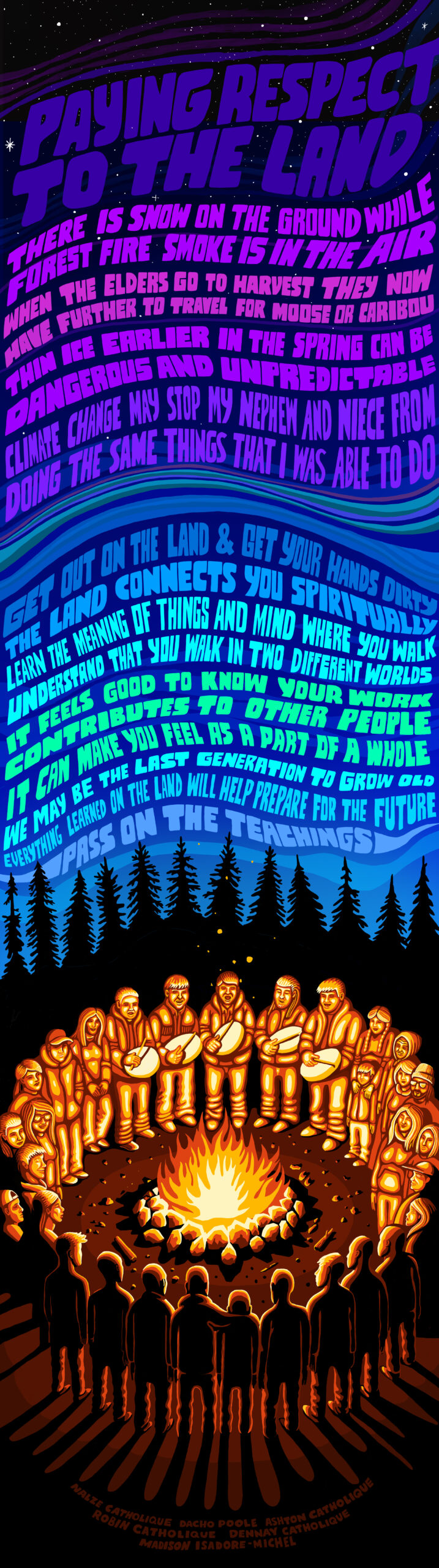

This visual summary was created by the participants of this case study.

By integrating skill-building and cultural healing via land-based learning and cultural exchange, the camps support holistic learning about climate change, while centering Dënesųłıné learners within their own communities, cultures, knowledge systems, and territories.

This case study undertook a participatory workshop with land-based camp attendees.

The workshop to explored the young people's concerns about climate change, their memories of land camps, and their most significant learnings about the land-based education camps.

The case study shows that young people are concerned about climate change and its impacts on their community’s way of life, despite that their contributions to climate change are relatively minimal. Based on stories from their Elders and their experiences on the land, young people were familiar with various climate impacts in their region, including lower water levels, increased fires, invasive species, declining caribou, thinning ice, and changing seasons. These changes create dangerous conditions for travelling on the ice and difficulties harvesting.

The young people understood these changes as impacting their community’s entire way of life. As “Caribou People,” they wondered who their community would become if the caribou migration left their region. They expressed fear for subsequent generations, who may not have the same experiences and practices that were important to them.

“Our way of life is just going to change. We won’t be able to live how we are supposed to be living. Like apparently we are called ‘Caribou People,’ but how can we be called Caribou People if there aren’t any caribou around?” – Madison

“It's a sad reality because a lot of cities don’t take climate change seriously because it’s not affecting them how it’s affecting us.” - Robin

The young people also understand climate impacts as combining with intergenerational trauma stemming from colonization to deeply impact young people, including their wellbeing and future prospects.

In light of these realities, land-based stewardship camps reinforced for young people the importance of “paying respect to the land,” a phrase that they repeated often and became the title of the mural that is a visual summary of this case study.

For young people in Łutsël K’é Dene First Nation, respect for the land is both a value and a practice, and respect is mutual: take care of the land, and it will take care of you.

Spending time on the land provided them with a stronger sense of identity, as they felt more connected spiritually and emotionally.

“I felt more connected with my mind and my body when I was out on the land. And when I got disconnected with the land I felt like I didn’t know who I was. So that’s what the camps did to me. It made me feel like I was more of a bigger person.” – Madison

For the young people, respect is both a value and a practice. It involves everything from cleaning up after yourself to ensuring against over-harvesting. Respect also involves repaying the land through prayer, spruce boughs, and tobacco offerings. In the face of climate change, paying respect means learning to “read the land” and adapt to changes by learning from Elders’ stories and archives of Dene knowledge. The camps helped young people read the land and learn to care for it.

At land-based camps, climate education holistically incorporated practical skills, western scientific knowledge, language learning, and cultural practices, which young people understood as collectively supporting mutual aid within the community. Here, climate action is not an individual matter but a collective and community endeavour.

The MECCE Project is grateful to researchers at Cape Breton University, the Łutsël K’é Dene First Nation, and the Thaidene Nëné Department for leading this case study

WATCH PLACES, COMMUNITIES, STORIES

Quality climate communication and education fosters relationships with places, communities, and stories. Learn more in our popular video.